Quilon

Breaking into the Indian Ocean

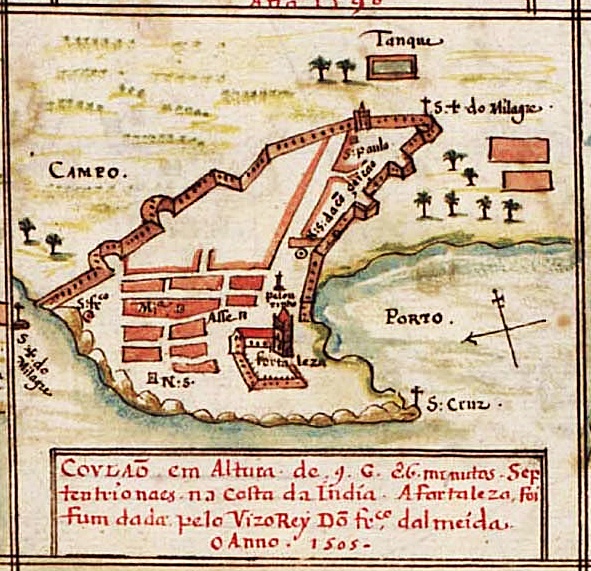

In Quilon, as in Cochin, Elmina, and Recife, the Dutch followed in the footsteps of the Portuguese. In 1503 Afonso de Albuquerque established a factory at Quilon and signed a treaty with the ruling family, marking the start of Portuguese efforts to control shipping in the region and monopolize the Malabar pepper trade. With roots stretching back to antiquity, Quilon (also known at the time as Coylan, Koylang, and today as Kollam) had long been an important port town on the Malabar Coast but had lost ground since the fourteenth century to Calicut—the main Portuguese rival in the region. Though Cochin and Goa remained the more important centers of Portuguese power in India, the factory at Quilon grew into a substantial fort that supported Portuguese commercial and naval operations for over 150 years.

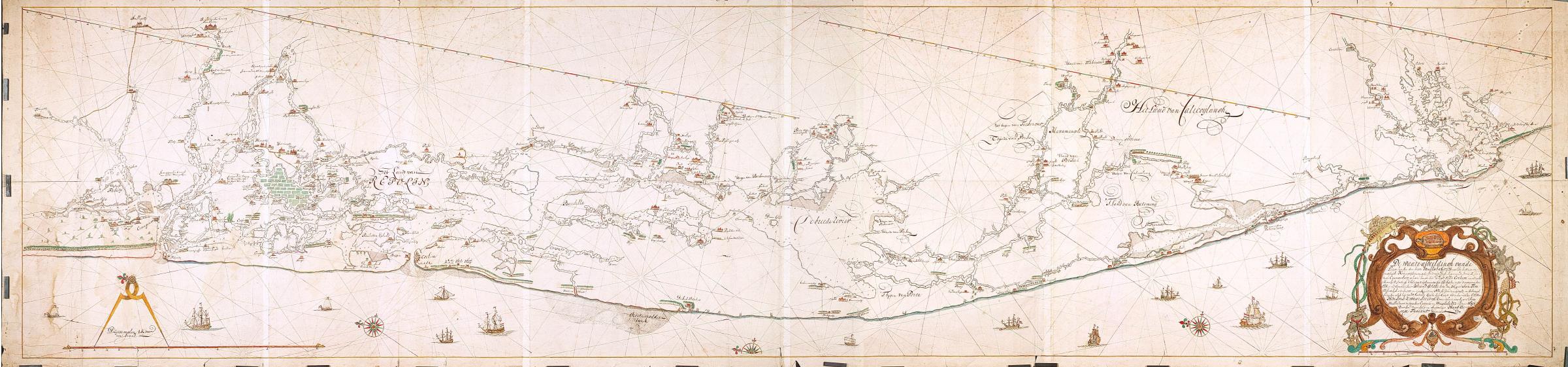

In 1596, Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerario introduced Dutch readers to the geography and commercial opportunities of the Indian Ocean. Van Linschoten had secretly copied the maps and navigational charts of his former employer, the Portuguese archbishop of Goa. Armed with this information, Dutch merchants soon launched several expeditions to South and Southeast Asia, eventually forming the VOC which would supplant the Portuguese as the primary maritime force in the Indian Ocean. By the time the map below was made, around 1623, the Dutch had vastly expanded their knowledge of the Ocean’s physical and political geography and acquired a network of trading posts across the region.

The VOC’s strategy for displacing the Portuguese from the Malabar coast hinged on effective alliances with Indian polities. The most important Dutch allies were the Zamorins of Calicut, whose commercial dominance over the region had suffered significantly from the arrival of the Portuguese. A joint expedition succeeded in the conquest of the Portuguese fort at Cochin, effectively ending Portuguese maritime supremacy in Malabar.

The VOC In Quilon

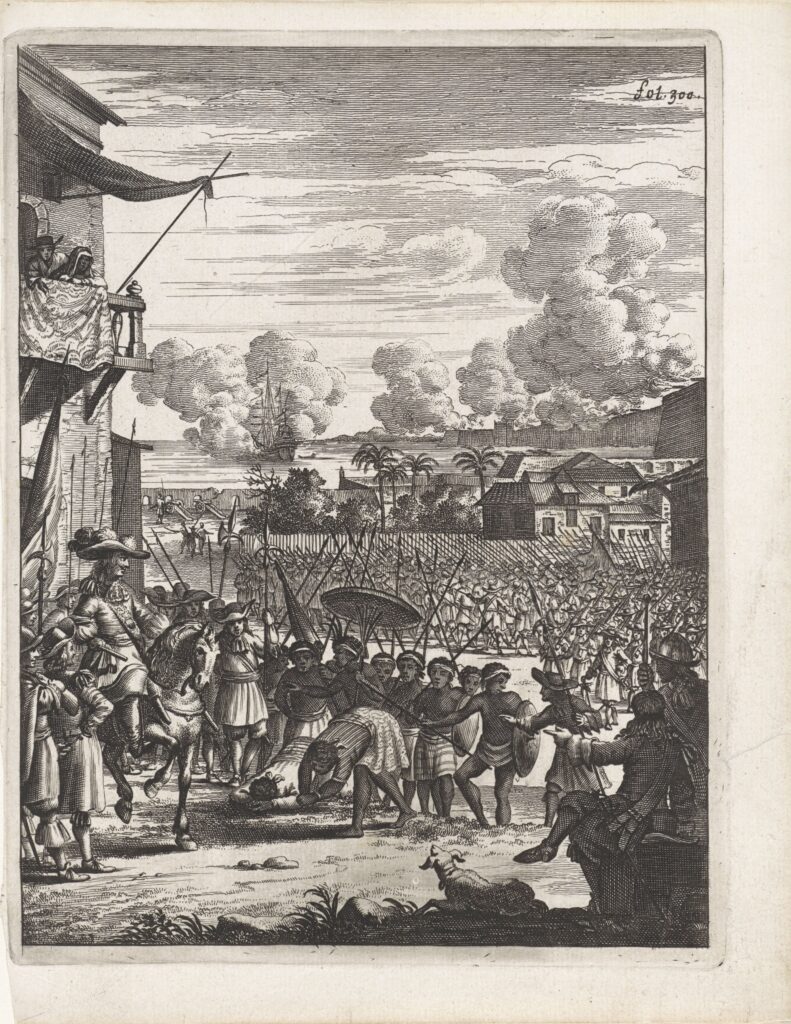

Having successfully displaced the Portuguese from Ceylon, the VOC turned its attention to the Malabar Coast in the 1650s. The company initially captured the fort at Quilon in 1658 but the new Dutch commander was ambushed and killed while out for a walk and the fort was returned to Portuguese control. News of an imminent peace treaty between Portugal and the Dutch Republic spurred the VOC to launch another offensive while they still could. In December 1661 a large fleet under command of Rijckloff van Goens returned to Quilon and recaptured the fort. Quilon became the VOC headquarters in Malabar until the conquest of Cochin two years later.

Not all Indian polities supported the Dutch takeover. The Queen of Quilon put up strong resistance to the VOC forces, eventually agreeing to sign a peace treaty only once the Portuguese had surrendered. The treaty roughly continued the arrangement enjoyed by the Portuguese, awarding the Dutch exclusive trade rights and jurisdiction over the fort in exchange for regular payments. The VOC also agreed to indemnify the Queen of Quilon for damages inflicted during the conquest.

As with all things, there were dissenting opinions within the VOC regarding the importance of Malabar and the best strategy for securing it. Many within the VOC hoped to take over the Portuguese monopoly of the Malabar pepper trade. Others saw the strategic importance of Malabar for securing the company’s conquests in Ceylon and controlling shipping lanes to the East Indies. Rijckloff van Goens advocated an aggressive and militaristic policy, successfully convincing the directors that the cost of maintaining permanent fortifications in Cochin and Ceylon could be offset by the local trade returns. Others, including some of Van Goens’ successors, advocated for a less costly approach centered on trade and minimal intervention. As it turned out, the Dutch had overestimated the strength of both the Portuguese monopoly and their claims to Indian territory. Local trading and smuggling made the pepper monopoly unenforceable, while Dutch claims to sovereignty or jurisdiction held little currency beyond the walls of their forts. Quilon and the VOC’s other Malabar forts increasingly became a financial burden over the eighteenth century, while the company proved unable to compete militarily with the expanding state of Travancore to the south. Declining revenues led the VOC to decide in 1793 to sell its holdings at Quilon and all other forts besides Cochin. In 1795, the Kew Letters transferred all Dutch holdings in Malabar to Britain, in order to prevent them from falling into French hands.

Nieuhof in quilon

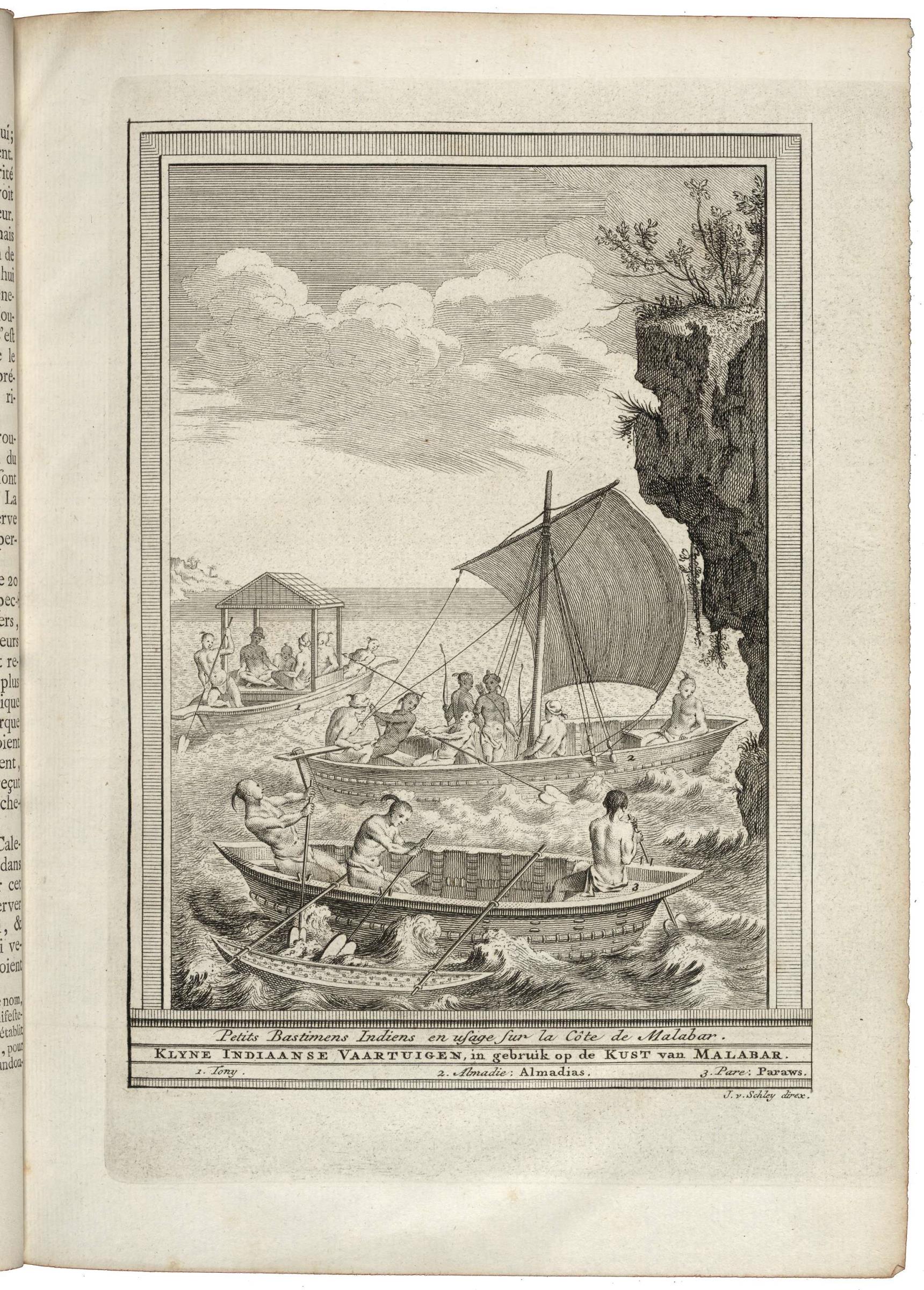

The famous Dutch traveler and writer Johan Nieuhof accompanied the Van Goens expedition and spent some time working for the VOC in Quilon. Nieuhof recorded his impressions of the city and its environs in his lengthy travel narrative Zee- en Lant-Reise door verscheide Gewesten van Oostindien (1682). Nieuhof enthused about the quality of the air and land around Quilon, which he reckoned among the most healthy and fertile of India. The area around the city was densely planted with lemon, mango, and other fruit trees, with the region’s valuable pepper plantations situated further inland. Nieuhof may have been reminded of home when he wrote approvingly that the land in the coastal region was extremely flat and broken up by many small waterways that made it easy to sail up to Cochin or Cranganor.

Nieuhof also wrote approvingly of Quilon itself. The city was surrounded by a stone wall about 18-20 feet high and a “large and pleasant” outer settlement that the Portuguese called “Koylang Chyna”. Quilon itself was divided into Upper and Lower Quilon. The royal family had its residences in the former, while the Portuguese occupied Lower Quilon which was situated closer to the sea. Nieuhof described several large buildings including the Portuguese governor’s lodge–the “oldest and strongest” in Malabar–which was situated by the sea, clad with coconut tree leaves, and boasted three tiled towers. Behind the Portuguese buildings lay a large and thriving garden of coconut and fruit trees. The local houses, Nieuhof recorded, were impressive multi-story stone buildings attached to large gardens full of trees, fruits, and herbs. Wells and cisterns provided clean fresh water that compared favorably with the brackish water of the coastal lagoons and river. Nieuhof reckoned the harbor was highly suited to smaller craft, but large vessels would struggle with a sharp southerly wind that might push them onto the “extremely rough and sheer” cliffs and rock shoals along the coast.

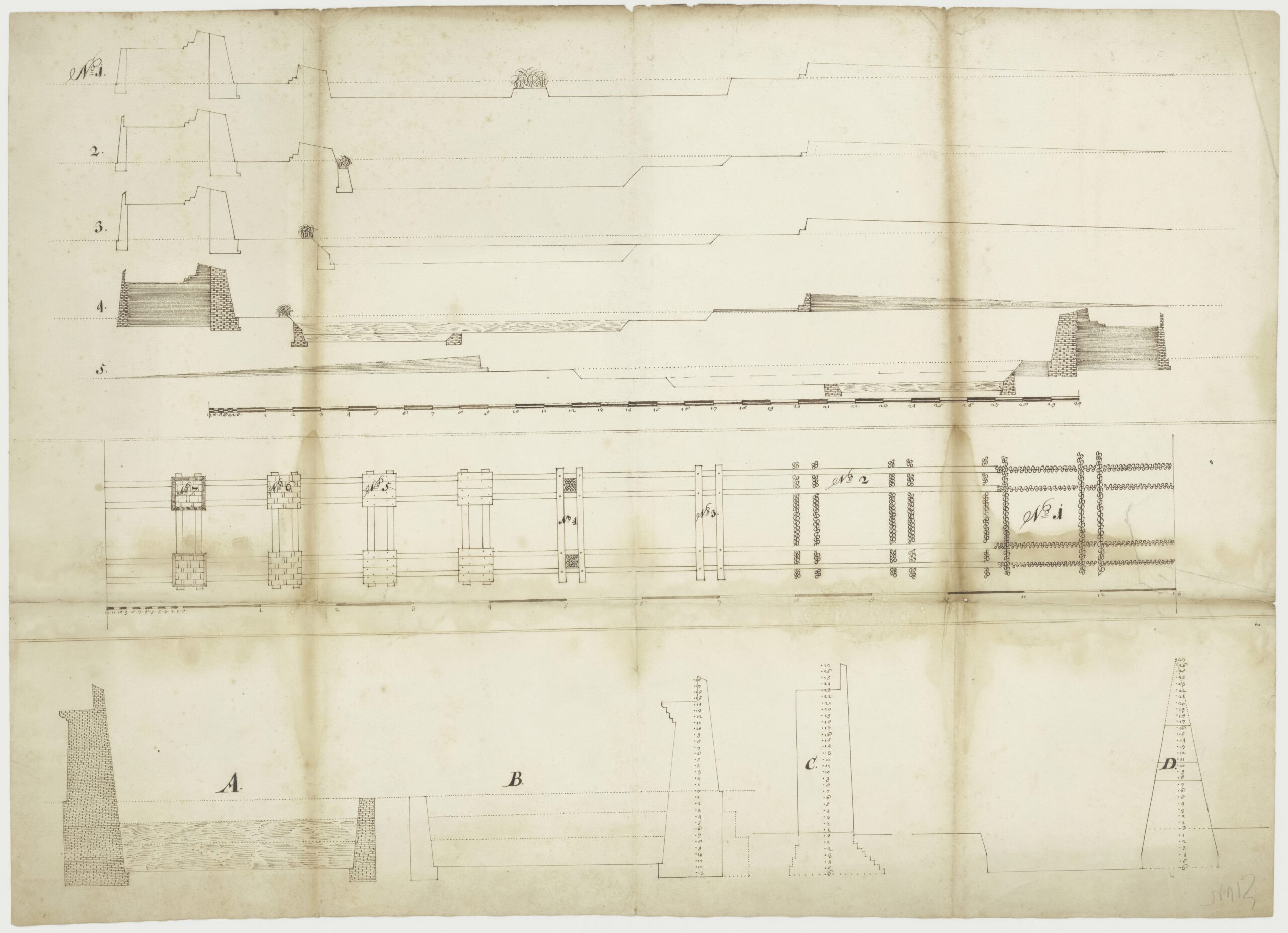

Rebuilding the fort

After capturing Quilon, Nieuhof reported, the VOC gave orders to raze the city “almost entirely” to the ground. The Portuguese and the Franciscans had left behind a monastery and no fewer than seven churches. One church belonged to the Saint Thomas Christians, who traced their history in the region back to the apostle Thomas. The VOC had little interest in maintaining these expensive Catholic buildings and decided to demolish almost “all houses, churches, and communal buildings to the ground.” The governor’s lodge, the St Thomas church, and a few of the most valuable houses were spared and brought into the grounds of a much smaller and more easily defended fort strengthened by the construction of additional walls. Continued efforts to economize led the VOC to plan another round of renovations to further shrink the fort at the start of the eighteenth century.

Further Reading

H. K. s’ Jacob, De Nederlanders in Kerala 1663-1701: De memories en instructies betreffende het Commandement Malabar van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (’s-Gravenhage: Nihoff, 1976).

H. K. s’ Jacob, The Rajas of Cochin, 1663-1720. Kings, Chiefs and the Dutch East India Company (New Delhi 2000).

Binu John Mailaparambil, Lords of the Sea: The Ali Rajas of Cannanore and the Political Economy of Malabar (1663-1723) (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

A. das Gupta, Malabar in Asian Trade, 1740-1800 (Cambridge 1967).

K. N. Chaudhuri, Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).